Partners in Art and Religious Propaganda

About the Cranach Workshop

Workshop Structure

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s many high quality portraits of Luther offer insight into how the Cranach family’s workshop functioned. Click to view an Interactive Timeline of Cranach’s portraits of Luther. In order to produce so much art while maintaining Cranach’s standard of quality, the workshop hired many employees such as Cranach’s sons, Hans and Lucas the Younger. Lucas the Younger was first mentioned as a member of the workshop in 1535, and assumed more responsibility when Hans died suddenly in 1537 while traveling in Italy. Lucas the Younger succeeded his father as director of the Wittenberg workshop in 1544.[1]Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980), 79.[2]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71.

Cranach also employed journeymen and court painters on a temporary basis and apprentices who studied with Cranach, and assisted in producing the artworks.[3]Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 287. Apprentices practiced by copying or making variations of the existing artworks before being allowed to work more creatively. At the end of their apprenticeships, “only the most skilled painters might be permitted to produce paintings that received the serpent signature as an indication of quality.”[4]Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 282, 283. In 1542, during a time of high productivity, the workshop’s records indicate employing “both [Cranach’s] sons, several qualified journeymen, as many as six workshop assistants and three apprentices plus carpenters, woodcarvers and zubereiter,” who applied the ground and gilding to a painting. [5]Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 282, 287.

Attribution and the Cranach Serpent Insignia

Because the Cranach Workshop employed so many artists who strove to create very similar products, attribution to individuals in the Workshop can be difficult. Cranach’s sons, Hans and Lucas the Younger, both worked and trained in the family studio in Wittenberg from a young age. [6]“Lucas Cranach the Younger.” Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum. Accessed September 27, 2021. … Continue reading The men were “eager to emulate [their] father,” so scholars have struggled assigning attribution to the sons or the father.[7]Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980.), 101. Many works from the Cranach Workshop are also attributed to the “Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder” or “Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Younger” to account for the contributions of the Workshop’s employees and uncertainty about the artist.

Though attribution to the individual Cranach family member may be difficult, the workshop’s signature makes identifying a piece produced in the Cranach workshop simple. A winged serpent holding a ring in its mouth is the workshop’s quality seal and legal signature.[8]Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 292.[9]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71. The insignia comes from Cranach the Elder’s coat of arms, given to him by his lord and later greatest patron, Elector Frederick Wise of Saxony. [10]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 1. Historian Steven Ozment writes that “The winged serpent signifies Chronos, the Greek god of time, a name Cranach occasionally applied to himself in an apparent humanistic embrace of antiquity. In classical mythology, a snake biting down on a golden ring represented eternal life, and bat wings were associated with dragons…The tribute was to Cranach’s ability to paint remarkably fast.” [11]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71. The insignia changed slightly over the years. The serpent can be seen with bird wings or bat wings, and with wings extended or dropped. After 1508, the bird wings were sometimes substituted for bat wings, a change that was adopted by the whole family in 1537 after Hans Cranach’s death. The serpent’s wings were shown extended prior to Hans’s death, then dropped after 1537 in commemoration of him. [12]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71.[13]Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980.), 79.

Gettysburg College’s Martin Luther is signed with the winged serpent insignia. The serpent has dropped wings and faces the right. It probably holds a ring in its mouth, but the fading has obscured it.

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Younger, Martin Luther, 1547, Gettysburg College.

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther, c. 1540,

National Museum in Wrocław.

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Martin Luther, 1547, Evangelische Kirchgemeinde Wörlitz.

Workshop Reputation

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s success as painter of the Reformers is due to his ability to create realistic and accurate likenesses of his subjects, a vital quality to producing successful propaganda.[14]Roth, Michael. “Reformation and Polemics.” Essay. In Renaissance & Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach. 91-121, (Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2016), … Continue reading He was also known for his talent of painting quickly, as is alluded in the Workshop’s insignia.[15]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71. Lucas Cranach the Elder became the Saxon court’s official “handler of Luther, an undertaking that positioned him also to become the painter of the Protestant Reformation.” The Saxon elector, a prince of the Holy Roman Empire, was Cranach’s most important patron.[16]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 1. Lucas Cranach the Elder played a key role in establishing Luther’s image and status as the leader of the Reformation.

The Cranachs in Service of Luther

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Luther collaborated for the first time in 1521 to make illustrations for Luther’s translation of the New Testament and publish Protestant interpretations of the Bible, some of which were printed on Cranach’s own printing press in 1522.[17]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 5. The pair and their families became fast friends. Cranach named Luther the godfather to his last child, “a merging of their two families as well as their talents in the cause of reform.” [18]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 5. The Cranach family’s workshop and Luther worked closely together until Luther’s death.[19]Muhl, Arnold et al. Martin Luther: Treasures of the Reformation. First edition. (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2016), 212.

Both Cranach and Luther were working in Wittenberg when they began working together, considered the “birthplace of the Lutheran Reformation.” Cranach’s most well-known workshop was located here. In 1534, the complete German Bible was published with 123 of Cranach’s illustrations.[20]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 133. Cranach had done portraits in 1520 of Luther before officially partnering with him, on the recommendation of Albrecht Dürer. Dürer feared that Luther may be killed after the publication of the 95 Theses, making the promotion of Luther’s reputation all the more urgent.[21]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 126

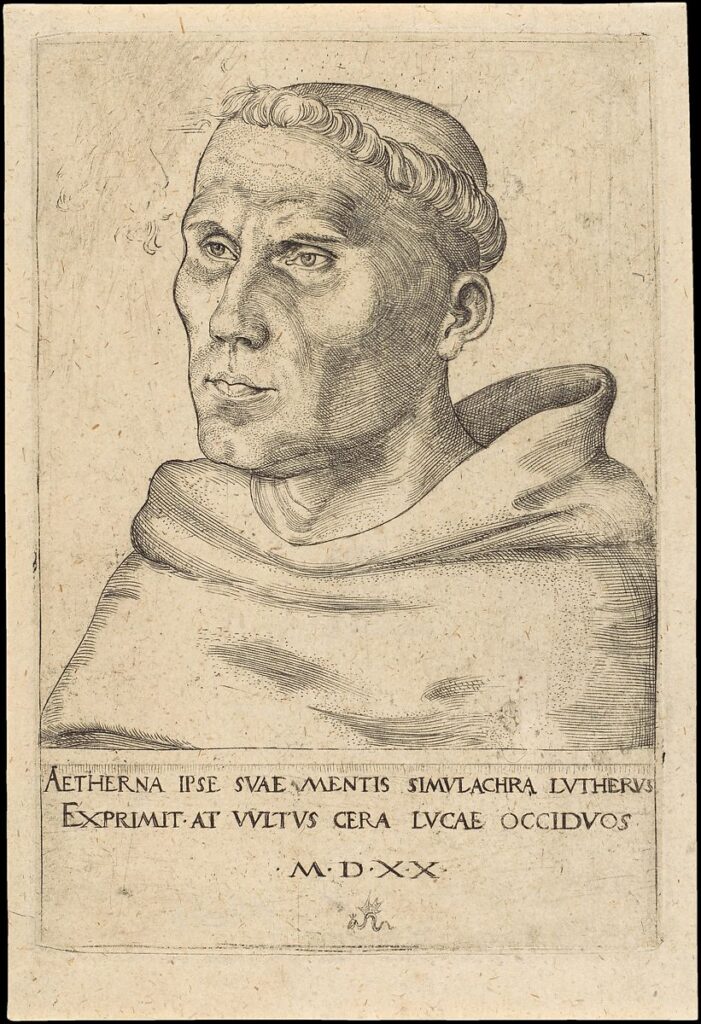

Cranach’s first image of Luther was an engraving, referencing Dürer’s style, called Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk. Cranach then produced a second portrait where Luther is depicted in a Saint’s niche with an open Bible in his hand, which was better received by the public, perhaps because he was given a Bible as a sign of credibility.[22]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 130. This image became Luther’s official court portrait and gave the Reformation a face; “the image of a holy man with an open mind, obedient will, and God-fearing heart.”[23]Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 130.

Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/358260

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1854-1113-232

References

| ↑1 | Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980), 79. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑9, ↑11, ↑12 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71. |

| ↑3 | Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 287. |

| ↑4 | Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 282, 283. |

| ↑5 | Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 282, 287. |

| ↑6 | “Lucas Cranach the Younger.” Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/cranach-lucas-younger. |

| ↑7 | Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980.), 101. |

| ↑8 | Heydenreich, Gunnar. Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques and Workshop Practice. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007), 292. |

| ↑10 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 1. |

| ↑13 | Schade, Werner. Cranach, a Family of Master Painters. Translated by Helen Sebba. (New York, New York: Putnam, 1980.), 79. |

| ↑14 | Roth, Michael. “Reformation and Polemics.” Essay. In Renaissance & Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach. 91-121, (Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2016), 95. |

| ↑15 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 71. |

| ↑16 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 1. |

| ↑17, ↑18 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 5. |

| ↑19 | Muhl, Arnold et al. Martin Luther: Treasures of the Reformation. First edition. (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2016), 212. |

| ↑20 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 133. |

| ↑21 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 126 |

| ↑22, ↑23 | Ozment, Steven. The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation’. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 130. |